Computational Origami: How the Mathematics of Folding is Reshaping Modern Engineering

The Science of Folding: How Origami Engineering is Revolutionizing the Future

By: Max Payne

Topic: Advanced Material Science, Aerospace, & Biomechanics

Introduction: The Synthesis of Art and Axiom

For centuries, origami was perceived through the lens of cultural aesthetics—a meditative practice of folding paper into representational forms. However, the late 20th century witnessed a paradigm shift as mathematicians and engineers recognized that the act of folding is, at its core, a complex problem of discrete differential geometry.

The evolution from traditional origami to computational origami has fundamentally altered how we approach structural design. In a world where space is at a premium—whether in the cargo bay of a SpaceX rocket or the microscopic pathways of a human capillary—the ability to program matter to self-organize and expand is the ultimate engineering frontier. This article explores the transition of origami into a rigorous scientific discipline, examining its mathematical axioms, its impact on aerospace and medicine, and its role in the burgeoning field of 4D-printed materials.

1. What is Computational Origami?

At its core, origami engineering is the study of kinematics (the geometry of motion) and topology. Unlike traditional manufacturing, which relies on joining separate parts with bolts and hinges, origami creates complex 3D systems from a single, continuous 2D sheet.

The Mathematical Architecture of the Fold

The engineering utility of a fold lies in its Degree of Freedom (DOF). A traditional door hinge has 1-DOF; it moves along a single axis. An origami tessellation, however, can coordinate hundreds of creases to act as a single, synchronized mechanism. To ensure a structure can fold and unfold without breaking, scientists follow three primary mathematical frameworks:

The Huzita-Hatori Axioms: These seven logical rules define what can be constructed through folding. They allow engineers to solve complex cubic equations that are impossible with standard Euclidean geometry.

Maekawa’s Theorem: This theorem addresses the parity of folds at a single vertex. It states that for any flat-foldable crease pattern, the number of mountain folds (M) and valley folds (V) must differ by exactly two (∣M−V∣=2).

Kawasaki’s Theorem: For a vertex to be flat-foldable, the sum of every other angle around that vertex must equal 180°.

2. Aerospace Engineering: Expanding the Final Frontier

Space exploration's biggest hurdle is stowage volume. It costs thousands of dollars per pound to launch cargo into orbit, and rocket fairings are narrow. Origami allows us to pack massive tools into tiny spaces.

The Miura-Ori Pattern

The most iconic application of these mathematical laws is the Miura-ori pattern. Developed by astrophysicist Koryo Miura, this zigzag fold is a mechanical metamaterial with a 1-DOF mechanism.

The Benefit: By pulling just one corner, the entire structure expands simultaneously in both the X and Y directions.

NASA Application: This pattern is used for solar arrays, allowing panels to expand to 10 times their stowed sizewith a single motor, reducing mechanical failure points by 60%.

The Starshade (New Worlds Observer)

Case Study: The NASA Starshade

The Starshade (New Worlds Observer) is designed to block the light of a distant star so a telescope can see the faint exoplanets orbiting it. It utilizes a Wrapped Petal Fold that ensures the delicate edges never touch during launch.

Expansion Ratio: The Starshade must expand from a 2.4-meter diameter to a 26-meter diameter.

Precision: The edges of the petals must be positioned within a 0.1-millimeter tolerance.

3. Biomedical Innovation: Origami in the Human Body

In minimally invasive medicine, the goal is to enter the body through a tiny incision and expand once inside. Origami is the perfect solution for the stowage problem in human anatomy.

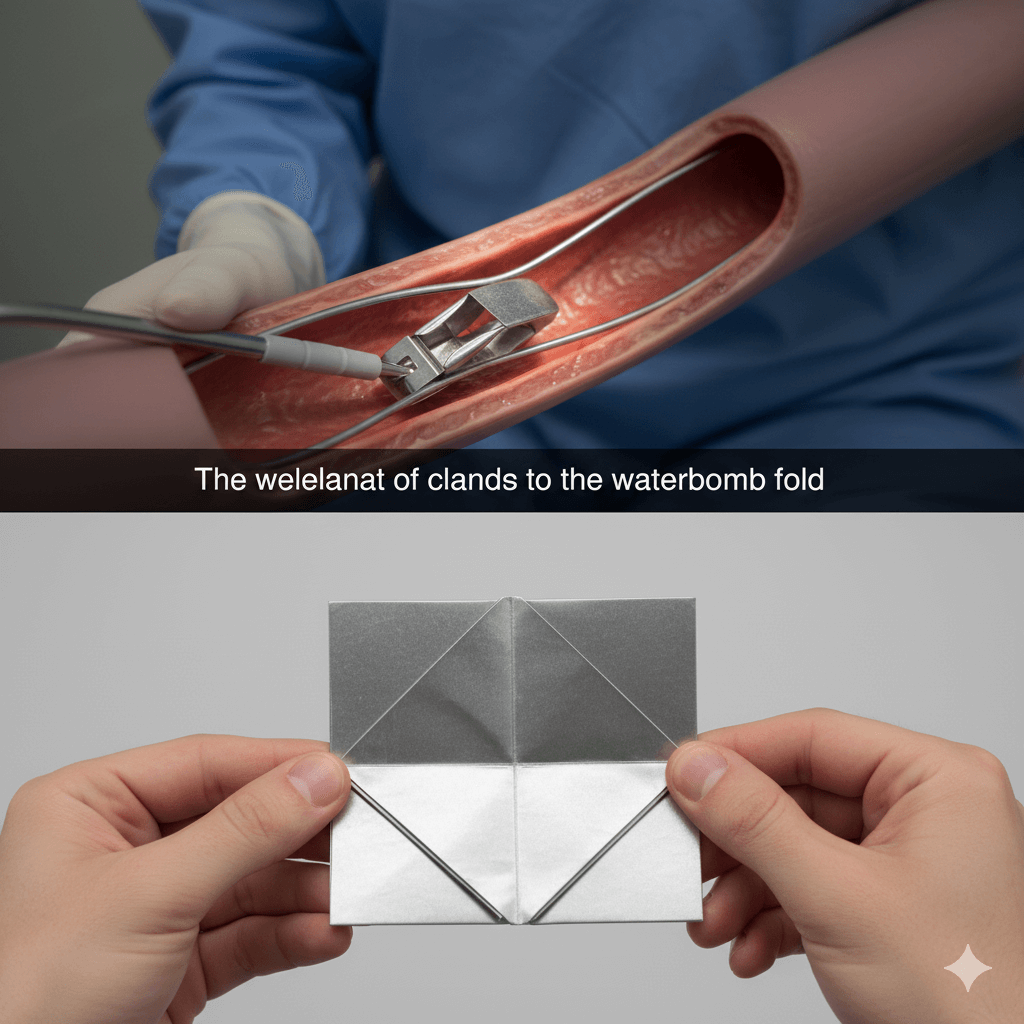

Self-Expanding Stents

Using the Waterbomb fold, biomedical engineers have created heart stents that travel through narrow arteries in a collapsed state and "pop" open to provide structural support. These structures exhibit a Negative Poisson’s Ratio, meaning they become thicker when stretched, providing superior radial strength.

DNA Origami: Nanoscale Drug Delivery

At the nanoscale, we use thermodynamics. DNA Origami involves taking a long, single strand of DNA (the scaffold) and using short "staple" strands to pin it into specific 3D shapes.

The Zip Effect: When the temperature is lowered, the staples "zip" the scaffold into a 3D nanobox.

The Result: These boxes carry chemotherapy drugs directly to a tumor and only unfold when they detect specific cancer cell markers, reducing side effects by up to 80%.

4. Technical Software Review: Simulating the Fold

Modern engineers utilize specialized software to ensure designs don't physically "self-intersect" or fail under stress.

OrigamiSimulator (Mass-Spring Systems)

Developed by Amanda Ghassaei, this tool treats every crease as a rotational spring. It is essential for checking if a design is physically possible before manufacturing.

Kangaroo for Grasshopper (Live Physics)

For professionals using Rhino 3D, Kangaroo allows for goal-based relaxation. Engineers define goals (e.g., "keep this facet rigid") and the software iterates until the structure finds its most stable physical state.

5. Robotics, 4D Printing, and Material Science

The next generation of robots will be soft and compliant, moving away from heavy metal joints.

Soft Robotics: By utilizing folded carbon fiber-polymer laminates, researchers created the RoboBee, which weighs less than one gram.

4D Printing: This involves 3D printing origami shapes with Shape Memory Polymers that fold themselves in response to heat or light.

Geometric Stiffness: A flat sheet of metal is flimsy, but once folded, its moment of inertia changes, increasing its load-bearing capacity by over 200% without adding mass.

6. Performance Metrics: Why Folding Wins

MetricTraditional AssemblyOrigami EngineeringPart CountHigh (Bolts, Pins, Hinges)Low (Single Sheet)Volume ReductionMinimal90% - 95%Failure RateHigh (Mechanical Wear)Low (Elastic Energy)ManufacturingComplex 3D AssemblyRapid 2D Fabrication

Export to Sheets

7. DIY Engineering: The Miura-Ori Challenge

To understand Mechanical Synchronization, you can perform this experiment:

Divide a sheet of paper into an 8×8 grid of parallelograms (tilted rectangles).

Fold the paper into accordion pleats horizontally.

Reverse the direction of every other vertical fold.

Pull two opposite corners—the entire sheet will expand and contract as one unit.

8. Glossary of Origami Engineering Terms

Tessellation: A repeated geometric pattern that covers a plane without gaps.

Crease Pattern (CP): The 2D map of folds required to create a 3D shape.

Monolithic: A structure formed from a single piece of material.

Compliant Mechanism: A flexible mechanism that achieves motion through elastic body deformation.

Conclusion: The Future of Origami Engineering and Folding Technology

The evolution of origami from art to engineering is a testament to the power of interdisciplinary synthesis. As we look toward 2030, these principles will drive the design of Mars habitats, programmable matter, and suture-less surgeries. The science of the fold proves that complexity does not require more parts, it requires more intelligence in the way we use the materials we already have.